Or, If You’re Expecting an Inside Look into the Avant-Garde School (or the ’80s Goth Band) You Might Want to Manage Your Expectations

When the word Bauhaus is mentioned, certain things inevitably come to mind. A collection of simple, but breathtakingly designed objects. A streamlined building composed of concrete, steel, and glass. A progressive art school filled with exceedingly creative (and slightly wild?) art students. You might even be picturing paintings or textiles featuring geometric shapes and vivid primary colors, or patterned wallpaper, or distinctive graphic design. The list goes on. But when it comes to FAÇADE, the Bauhaus you get—the Berlin Bauhaus in 1933—might not be quite the Bauhaus you’re expecting. Here are five things you should know about the Bauhaus in regards to FAÇADE.

1. 1933 is not 1919

In the event the word Bauhaus conjures nothing in your mind, here’s a brief primer. Established in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, the Bauhaus was a school of art and design conceived to combine instruction in both fine and applied arts, under an umbrella of architecture and design, with the goal of designing functional, but aesthetically pleasing, household objects that could be mass produced and made available to the common man. The name Bauhaus, which translates as “house of building,” is a play on the German word Hausbau, or “house-building.”

The political and cultural climate in 1919 was quite different from that of 1933. The year 1919 marked the beginning of the Weimar Democratic Republic in Germany, which was characterized on the one hand by a parliamentary system with a president, abounding civil liberties, and a flourishing cultural scene, and on the other by political instability and social unrest, which, when complicated by tough economic times, gave rise to extremist movements like National Socialism. The Weimar Republic came to an end in early 1933 when Chancellor Adolf Hitler put his Enabling Act into action, which is where FAÇADE begins.

During its existence during the republic, the school moved from Weimar to Dessau and then to Berlin, and so in FAÇADE the Bauhaus is in the third of its distinct iterations: Bauhaus Berlin.

2. Bauhaus Berlin is not Bauhaus Weimar

Established in the same year and in the same city as the new Weimar Republic, the Bauhaus in Weimar embodied a similar spirit of renewal. The school was thereafter associated with the Weimar Republic.

Inspired by Expressionism, then de Stijl, then Constructivism, the Weimar Bauhaus and its unique program attracted the avant-garde from across Europe; at the same time, it drew criticism from the political right for coming across as too bolshevistic. When a right-leaning party gained the majority in the state legislative assembly in 1924, the school’s budget was severely cut, and the Bauhaus teachers agreed to move to a city governed by Social Democrats: Dessau.

3. Bauhaus Berlin is not Bauhaus Dessau

Bauhaus Dessau (1925–1931) was the Bauhaus in its prime. Gropius’s famous school building helped afford the unity of art and technology the school sought to have. In Dessau the school’s most famous products and buildings were created.

The Dessau Bauhaus retained its roster of renowned artist teachers, including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Oskar Schlemmer, giving the city a cache of fame.

4. A Socialist Reputation is a Hard Thing to Shake

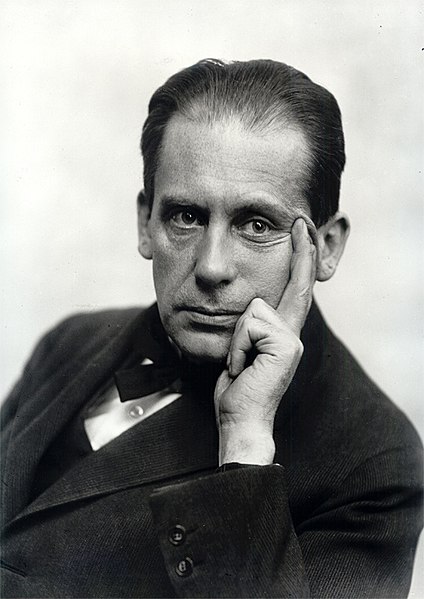

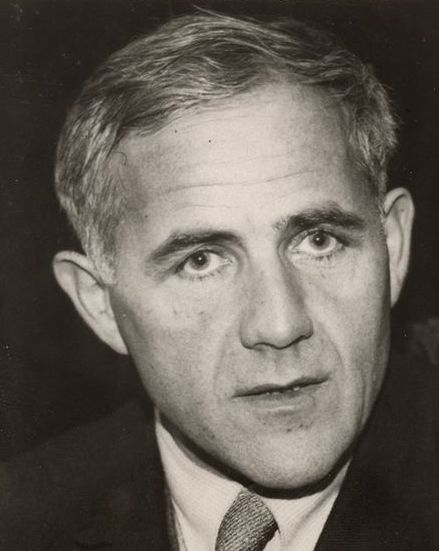

In 1928 Gropius turned over the directorship of the Bauhaus to the head of its architecture department, Hannes Meyer. While Meyer continued the Bauhaus’s design of protypes for mass production, his socialist leanings and philosophies eventually led to his dismissal by the Dessau city council in 1930. In came the school’s third director: architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

By this point the Bauhaus had long been controversial for its modernist style and internationalist philosophy, not to mention its reputation for embracing leftist politics. Mies van der Rohe claimed that his Bauhaus—and its modernism—was thoroughly apolitical; it was “a school of art and nothing more.” But by this time the Nazi party was already gaining ground in Germany. When a rightist majority in the city council voted to close the Dessau Bauhaus in 1932, there was little Mies could do but reopen the school as a private institution elsewhere. The Bauhaus was relocated to an refurbished telephone factory in Berlin in late 1932; in January 1933, Hitler was installed as Germany’s chancellor. And here is where the story of FAÇADE begins: at the beginning of many endings to come.

5. Bauhaus Berlin: Just a Brief Look

When FAÇADE opens and we get our first glimpse of the Bauhaus, it is already too late. There isn’t time to appreciate the whole of what the Bauhaus is, or has been, before the school is surrounded by state police trucks and raided. We are as helpless as Mies. We must read on to see what comes next for the Bauhaus, and what its fate might mean for Mies and other modernist artists in Germany.

p.s. If you really were hoping for a reference to the legendary post-punk band Bauhaus, the Goth pioneers originally named Bauhaus 1919 who were apparently inspired by the Weimar Bauhaus spirit, here’s a great tune: