Or, What Night Bitch and Bauhaus Master Gunta Stölzl have in common

In my novel FAÇADE the reader encounters German textile artist and Bauhaus Master Gunta Stölzl under extraordinary historical circumstances. But as a female artist and single mom, her need to overcome everyday obstacles in order to create resonates right up to the present.

Gunta Stölzl: Art as Life

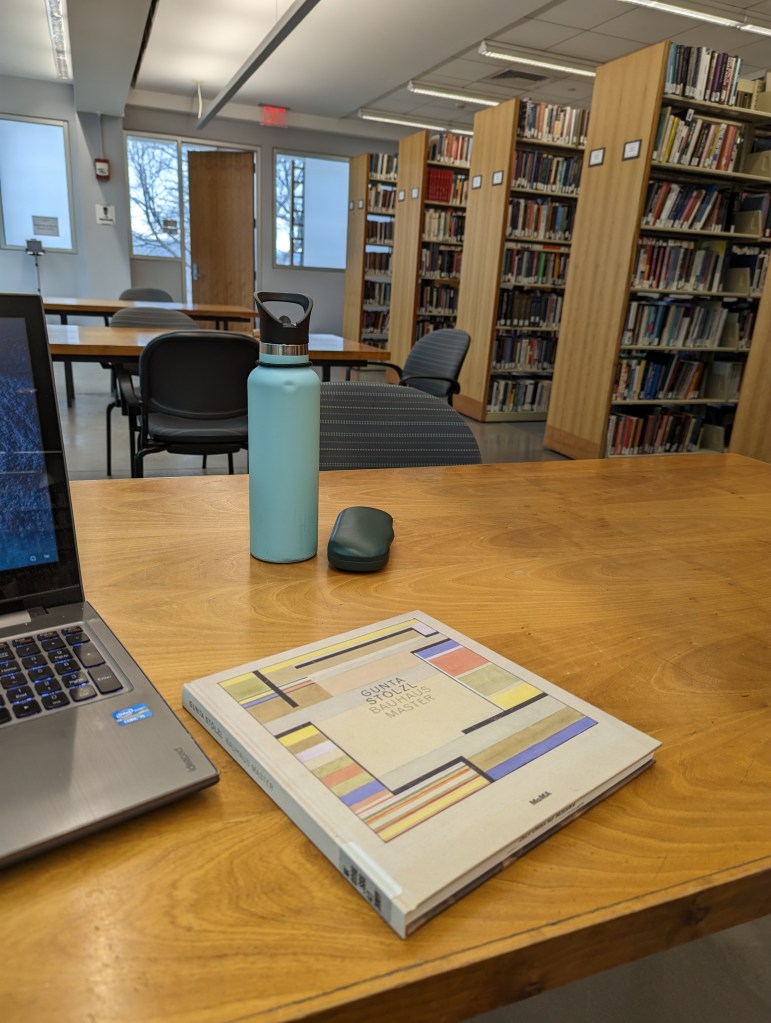

Reading Gunta Stölzl: Bauhaus Master, I learned this: in 1931, right in the midst of some very real persecution that involved having a swastika painted on her door and ultimately culminated in her dismissal from her teaching job, Gunta Stölzl executed a quite complex, innovative, and breathtaking wall hanging on a Jacquard loom. A similar story about Gunta was told by her youngest daughter Monika Stadler during a presentation at the Barbican Centre’s 2012 “Bauhaus: Art as Life” exhibition: in the thick of extreme personal insecurity right after she was forced to forfeit her German citizenship, Gunta created a 10-page picture book for her baby daughter Yael’s second birthday.

“To me,” says Stadler of the accomplishment and its timing, “this is ‘Art as Life.'”

It paints quite a picture of what being an artist is. Or at least what life as an artist was for Gunta Stölzl. But perhaps a little background is called for.

Who is Gunta Stölzl?

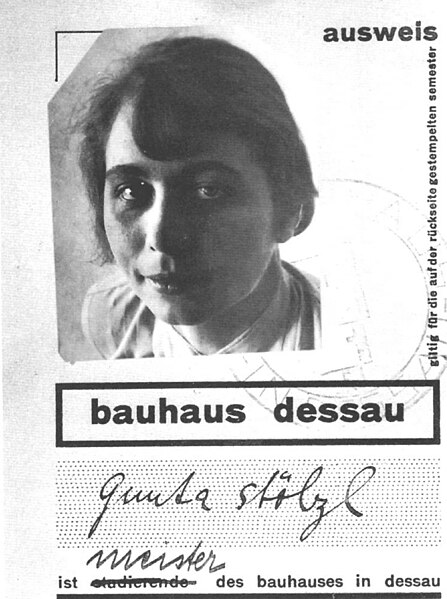

A tidy little summary: Gunta Stölzl (March 5,1897 – April 22, 1983), one of the Bauhaus’s earliest students and its first female Master, played a pivotal role in the advancement of textile arts at the school, both as a discipline and as a thriving workshop (the most profitable of all Bauhaus workshops, in fact). Her personal work is recognized as exemplifying Bauhaus style in regard to textiles.

She was the first woman to exhibit textiles at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. After her time at the Bauhaus, she ran her own successful weaving mills where she designed a multitude of commercial textiles; she received the “Grand Prix” at the ”Exposition Internationale de l’Urbanism et de l’Habitation” in Paris, and participated in numerous exhibitions in her later years until she passed away at the age of 86.

But real life is not so tidy, and Gunta’s was no exception. Enough that she was a female in the male-dominated art world; enough that, even at the supposedly forward-thinking Bauhaus, women had second-class status and were considered incapable of the rigors of the “masculine arts.” Enough that she had a baby, and brought that baby to work with her (gasp!). Gunta’s life in 1930’s Germany became very complex when she married Arieh Sharon, a Palestinian Jewish architect. And when that marriage failed and she was left to forge a life for herself and baby daughter, everything became very untidy indeed. But in the midst of all that real life, the art did not stop.

A Balancing Act

If you’re an artist, your art makes demands. It pulls on you. Part of your brain is always working on it, even if you’re stuck working on something else. Paying bills. Folding laundry. Cooking dinner. Having a full-on conversation with your spouse. The demands of life are almost always at odds with the demands of art, with the result of feeling pulled in two directions at all times. It would seem art and life are enemies. And so how do you find balance?

If you ask an artist like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the answer is simple. The work is primary. Nothing comes between him and it. Not boring errands, not paperwork, not even family relationships. And not political matters, either. Of course, it can be argued that Mies had the luxury of skipping the mundane stuff because he had someone else—usually Lilly Reich—to do it for him. And it can’t be discounted that Mies was a genius…and also a man. Who would bat an eye at a virtuoso hyper-focusing on his work? Who would interrupt Michelangelo to ask him to take out the trash?

But what about Gunta, single mother of a very young child? Gunta, whose mind was filled with complex patterns and ideas for incorporating synthetic materials like cellophane, but at the same time was in real danger of becoming stateless AND needed to get dinner on the table? In FAÇADE Gunta is a mentor to one of my main characters who is very much in need of advice on such matters. To write her I needed to know what that advice might be.

The question that really resonated with me was how to balance art and motherhood. It’s certainly no secret that the struggle is real for any working mother. Whether you are eschewing traditional roles by choice or being forced by financial necessity to work when you’d rather be home with your babies, wanting on the one hand to do meaningful work and on the other to be present for your children—each thing requiring the whole of you—puts you at a real risk of being torn in two. (I don’t mean to suggest that Dads don’t struggle, too—even in a traditional scenario where a mother stays home, the pressure to provide for a family can and often does dictate taking a job that pays over work that satisfies. How many would-be artists, musicians, writers, etc. in this scenario choose to shelve their dreams?)

Art, Motherhood, and Night Bitch

But, balancing art and motherhood. Twin powerful forces, diametrically opposed. The masterful novel Night Bitch by Rachel Yoder (the film adaptation starring Amy Adams was decent, too—did anyone else notice the amazing casting of the baby?) illustrates the disastrous impact of not balancing them, but choosing one over the other. The main character, facing the awful Sophie’s Choice of leaving her baby at daycare to continue as a working artist versus renouncing the work totally to become a full-time mom, initially tries the former, but cannot handle the agonizing guilt and longing. And so she settles on the latter: day after day after day with only a small child as company, subduing her creativity until it rears its feral head and quite literally takes her over. Mothering is primal, but Yoder seems to argue that the creative drive is, too.

Art Is Life

And so what would Gunta have to say about all of it? Here’s the rub about using historical figures in your stories: the things you have them say and do need to be plausible. And so I had to do my research carefully. I really was fortunate to be able to get my hands on the aforementioned book Gunta Stölzl: Bauhaus Master, which, besides including a number of her major works, also featured excerpts from Gunta’s journal and personal letters and some insights from Monika Stadler (who edited the work alongside her sister Yael—they also created this incredible website).

Having this glimpse into Gunta as a person was such a gift, and I hope FAÇADE does her justice. I realize that such a small portion of her life (1933-37, when Yael was a little girl and Monika had yet to be born) could never give a full portrait of who Gunta Stölzl was. But with any luck, I rendered her as someone capable of striking a balance (even an uneasy one) between art and life, because to her, the one is an inextricable part of the other.

2 thoughts on “How to Balance Creative Pursuits with Everything Else”