Or, How the Heirs of a Prominent German Jewish Art Dealer and Collector Keep Fighting the Good Fight

Nearly a century has passed since Nazi Germany waged a campaign against modern art and its creators, ultimately seizing artworks from German galleries, museums, and private owners (particularly Jewish owners) and auctioning them off to the profit of the regime. It may come as a surprise to many that in 2025 several restitution cases for Nazi-looted art remain unresolved.

When German gallerist and modern art dealer Alfred Flechtheim fled Nazi persecution in 1933, he lost hundreds of artworks—paintings by masters like Picasso, Seurat, Van Gogh, Klee, Kokoshka, Beckmann, and more. Some works from his galleries and private collection were sold under duress or out of desperation for income; others were stolen and sold off or donated. Many have wound up in German and American museums.

Flechtheim’s heirs would like these artworks back. They have in fact been seeking restitution of his art collection since the 1950s. But while they’ve managed to reclaim a few pieces, many more continue to be the subject of dispute all these years later.

Resolving the situation seems fairly cut and dried: the lost art should be restored to its rightful owners. But when nearly 100 years have passed, when documentation is scant or missing entirely in the wake of a world war, when an artwork has traveled a circuitous journey to land in the current owner’s hands, it’s not so easy to prove the circumstances under which the piece was lost to one and acquired by another. Complicate this with matters of law and politics, and it’s not hard to see how art restitution cases can drag on for years.

Issues of Provenance and Ethics

Determining the provenance, or ownership history, of museum-held objects is of course the museum’s ethical responsibility; ensuring artworks are legally and ethically acquired (i.e. that they weren’t, in their journey to the museum, ever stolen, expropriated, illicitly trafficked, or sold under duress) is also a wise move for warding off legal disputes. Once researchers investigate and document provenance, findings are often made public, both to facilitate further research and for the sake of transparency. But provenance research can be tricky, leading in some cases to dead ends and in others to murky waters.

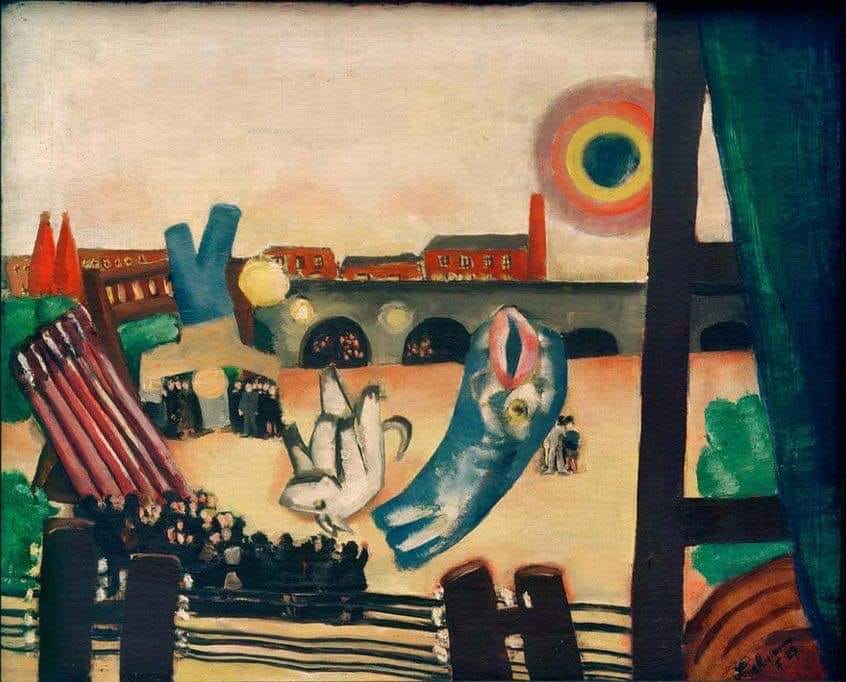

In the ongoing lawsuit brought by Flechtheim’s heirs against the state of Bavaria—concerning eight artworks formerly owned by Flechtheim and currently held by the Bavarian State Painting Collections (BSGS)—Flechtheim’s family argues that Nazi racial policies created the circumstances that forced him to lose these works of art: Flechtheim, a Jew, was disqualified from joining the Reich Cultural Chamber, an obligatory professional organization; his business was consequently forfeited and Aryanized, and he was forced to flee the country. Bavaria claims an entirely different provenance scenario: that the artworks in question (including Max Beckmann’s Chinese Fireworks, shown above) had been freely sold to a private owner in 1932 (a year before the Nazis came to power) who later donated them to Bavaria, making them the legitimate property of the BSGS. The Flechtheim heirs have challenged this sequence of events, but for legal reasons they’ve been blocked from accessing the existing documentation that would support this challenge. And their case lingers on, now nearly ten years in.

But just this February some quite incendiary information surfaced that could significantly undermine Bavaria’s credibility in the matter: the German publication Süddeutsche Zeitung reported that a leaked internal document suggests the BSGS has been knowingly holding hundreds of Nazi-looted artworks without disclosing this fact to the public or to heirs seeking restitution. In response to the report German Minister of Culture Claudia Roth accused the BSGS of “deliberate concealment” and a “lack of transparency.” An Art Review article says the leaked document names works in the BSGS holdings that had belonged to Flechtheim.

How the Flechtheim restitution case might resolve in light of this event remains to be seen. Berlin journalist and author Michael Sontheimer, in his March 26 online presentation on Flechtheim, commented on the obstacles faced by the art dealer’s heirs, saying it is unclear whether the family will succeed in getting justice if they continue to persevere.

“Hardly any documents from Flechtheim’s gallery have survived, and no written legacy existed despite intensive research. Much remains obscure, but one thing is beyond question: the Flechtheim case is the largest, but also the most complicated, case of art restitution still left in Germany.”

A Life Ruined, a Collection Scattered

In his lecture, organized by the Fritz Ascher Society for Persecuted, Ostracized and Banned Art and entitled, “ ‘There is something mad about the art:’ The German-Jewish Art Dealer Alfred Flechtheim and his Heirs’ Fight for Restitution,” Sontheimer enumerated the various legal and political challenges faced by Flechtheim’s heirs and others seeking restitution for Nazi-looted art. Sontheimer also painted a vivid picture of Alfred Flechtheim as a collector and dealer, who played a prominent role in the European art world in the 1920s representing and promoting both French avant-garde artists and German modernists, who established the legendary art publication Der Querschnitt (“The Cross Section”), and who opened art galleries in Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Cologne, Vienna, and Berlin.

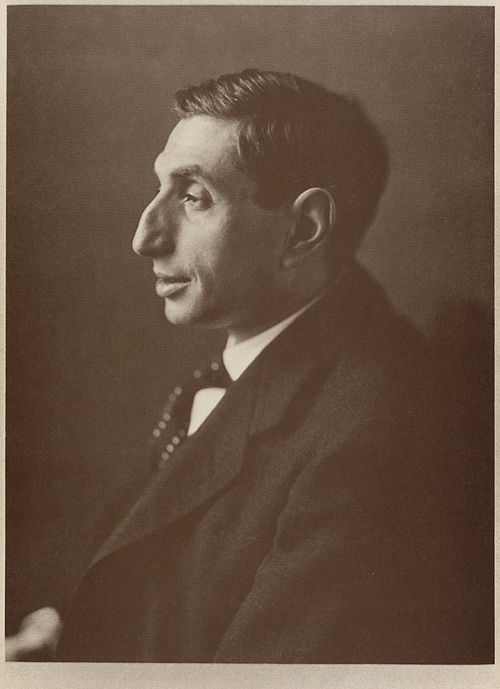

In FAÇADE, readers will encounter a historic 1933 exhibition of modern art in Berlin at the Ferdinand Möller Gallery. As a non-Jew, Möller was able to maintain his gallery during the Nazi era; he somehow even managed to continue exhibiting modern artworks as late as 1937. By contrast Flechtheim was immediately targeted as both a racial and a cultural enemy. The extent to which Flechtheim represented a double enemy to the Nazis can be clearly seen in the advertisement poster for the 1937 Nazi “Degenerate Art” exhibition: an antisemitic caricature of Flechtheim’s face looms behind a piece of the modern art he championed.

In 1933 Flechtheim fled Berlin for Paris and then London, where, destitute, he died in 1937 following an injury that led to sepsis. His widow Betty committed suicide in 1941 ahead of being deported to Minsk.

Left in the wake of these tragedies was the question of just how many works of art the Flechtheim collection contained. Estimates range from up to 300 to 300-plus artworks, not including the over-20-piece collection of colonial art from the global South now held in museums in Zurich, Cologne, and elsewhere.

“It is largely unclear which pictures were still hanging in Betti Fleschtheim’s apartment when the Gestapo sealed it,” said Sontheimer. “By this time the collection had already been scattered to the four winds.”

The Future of Art Restitution

With some enthusiasm Sontheimer referenced Germany’s new plan for restituting Nazi-looted art, put forth in January by the federal cabinet. Conceived in cooperation with the Central Council of Jews and the Jewish Claims Conferences—organizations devoted to seeking damages for survivors of the Holocaust—the plan includes the establishment of a special arbitration court that would allow victims of Nazi looting to seek arbitration without the current owner’s consent. While the move seems like a step in the right direction, the timing for action, according to Sontheimer, could have been a bit better.

“It would have made sense to pass a restitution law many years ago,” he said, noting that a proposal made by an outgoing government might not be prioritized by an incoming government (German federal elections were held on February 23).

When it comes to art restitution, said Sontheimer, complexities reign, particularly in a world that lately is concerned with so much else.

“There are no easy solutions,” he said, “and politicians do not have much to gain from the restitution of looted art. It is an issue that the majority of Germans simply don’t care about.”

But Sontheimer says he is maintaining hope, both for Flechtheim’s heirs and for all art restitution cases like theirs.

“The longer I was…writing about, doing research about, art restitution and about the case of Flechtheim, the more I got convinced that eventually all these paintings have to be given back.”